Heinz Alumnus Tomas Aftalion Is Leveraging Artificial Intelligence to Restore the World's Forests

By Jennifer Monahan

It’s a lesson many of us learned sitting in primary school classrooms: People need clean air to survive; trees make clean air; people need trees.

Amid widespread severe weather events, extreme temperatures, and raging fires, the effects of climate change are increasingly obvious. But saving the planet is a daunting, high-stakes challenge.

One company, Pachama, is trying to tackle that complex challenge with a combination of grammar school basics (people need trees) and cutting-edge technology—using machine learning to reimagine the carbon-capture industry. Their aim is to address climate change and protect life on Earth by growing the world’s forests.

Forests represent one of the most compelling opportunities for carbon sequestration at scale. The United Nations’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change recommended adding one billion hectares of forests to help limit global warming. Ecologists at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich found that the earth could support 0.9 billion hectares of additional forests—roughly equal the size of the United States—without disturbing existing urban or agricultural lands.

“In order to reach this number we need to radically improve upon how we do things,” said Tomas Aftalion (MSIT ’12, MISM ’15), co-founder of Pachama. “The challenge lies in the need for scale, and traditional methods involving manual verification and issuance will simply not suffice.” Pachama aims to emulate the playbook of Silicon Valley startups such as Airbnb and Uber, leveraging open markets to address the supply issue.

“Many technologies deployed for self-driving cars and current advances in AI can be repurposed for our mission,” Aftalion explained.

Their approach seems to have struck a chord. Investors include startup accelerator Y Combinator as well as Amazon Climate Pledge, Shopify, and Salesforce, among others.

The Johnny Appleseed of Tech

Johnny Appleseed—a real person who gained legendary folklore status for planting trees throughout the midwestern United States—accomplished in the late 1700 and early 1800s what Aftalion and his colleagues are trying to do on a global scale today.

In one recent effort, Pachama collaborated with Delta Land Services, LLC, on the Avahoula Climate Action Project. Their goal is to reforest an area greater than 5,400 football fields in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley.

The land is uninhabited. In addition to the immediate benefit of removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, replanting those 7,000 acres of deforested farmland will reduce erosion and chemical run-off to the Gulf of Mexico. It will create better habitats for wildlife and more jobs for those working in nurseries, planting trees, and executing logistical operations for the project.

Pachama contributes by using satellite imaging, remote sensing, and machine learning to identify, evaluate, develop, and monitor the project. Such tech-enabled forest carbon projects allow corporate or individual clients to invest directly in the work, and to get quantifiable and reliable results. Reliability has been a significant issue in the carbon credit industry; it represents another area where Pachama is using technology to help the environment.

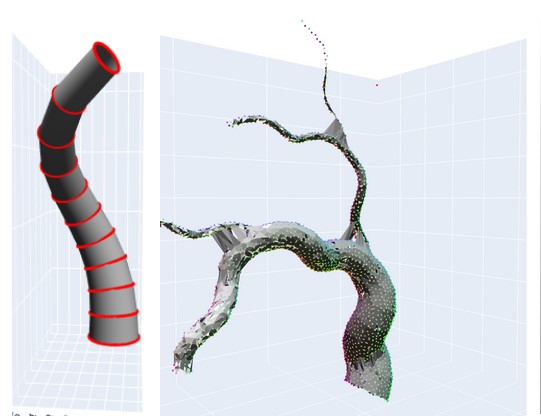

This video illustrates a high-resolution scan done with Velodyne LiDAR, an example of the technology Pachama uses in its work.

Carbon Credit Challenges

Burning fossil fuels (think power plants, where we get our electricity) and deforestation are two main sources of carbon dioxide emissions responsible for climate change. The idea of carbon credits is that companies can offset the harm they cause through these emissions by doing positive things to remove carbon dioxide—like planting trees. But the system is far from perfect.

In addition to reliability issues, the process of verifying a baseline carbon situation is labor-intensive, outdated, and expensive. Currently, scientists must travel to the project’s location and manually measure the biomass – the trees and living organisms in a given area.

Pachama aims to solve those challenges, as well.

The manual process doesn’t scale, and it’s one of the big bottlenecks. Coming from the tech world, I was thinking, ‘How can this be? It should be faster.’Tomas Aftalion

The tech skills Afatalion learned at Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy while pursuing master’s degrees in both Information Technology and also Information Systems Management have enabled his leading-edge solutions to climate change challenges at Pachama.

What we were learning in 2015 was so advanced for the time; it was at the cutting edge of what you could do with deep learning.Tomas Aftalion

Aftalion studied artificial intelligence, deep learning, cloud computing, and an array of electives that satisfied his thirst for knowledge across different disciplines and areas of interest.

“Heinz really prepared me by exposing me to the newest and most innovative work in various fields,” Aftalion said. “I was not yet thinking about Pachama, but tinkering with the idea of an aquaponics system. I took the social entrepreneurship class and covered many components that ended up being applied at Pachama.”

After working for a couple of years, Aftalion had a moment of insight.

“I realized there was an incredible opportunity to leverage deep learning, remote sensing, and finance to help out with the climate crisis,” Aftalion said. “My first idea was agricultural insurance. After meeting my co-founder, Diego Saez Gil, I realized the world of carbon credits presented a unique way to realign ecology and economy.” The duo shared a common vision of how technology could help humanity, and they got to work.

To address the challenge of reliability, Pachama created Dynamic Baselines, (now incorporated into their latest Project Evaluation Criteria 2.1), blending artificial intelligence (AI) with a concept used in scientific experimentation and medicine: a control group.

Baselines are a measure of what would have happened to a project without the carbon credit incentive. The industry has a financial incentive to over-credit by creating worse-than-reality baseline scenarios. Even with honest intentions, individual consultants could have differing analyses of the baselines for the same area, depending on what data they consider. And each project is considered on a case-by-case basis.

Pachama’s project evaluation criteria creates an algorithmic baseline, uses satellite data to observe actual emissions, and quantifies uncertainty into the equation. The company makes its methodology public and hopes it will become the industry standard.

Aguas do Rio Project

Pachama's Aguas do Rio (River Waters) project is located about two hours from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Transparency is desperately needed. The solutions we are providing have been well received by the market.Tomas Aftalion

“Transparency is desperately needed. The solutions we are providing have been well received by the market,” Aftalion said.

The company is also employing technology to improve efficiency and scalability. They use satellite observations and digital measurement to augment the manual biomass measurements. They have automated credit calculations and use digital reporting and verification platforms to help modernize the processes. Rather than rewriting the playbook for carbon credits, Pachama is applying technology to improve upon existing methods.

Beyond Carbon Offsets: Pachama Originals

With the Pachama Originals project, Aftalion said the company is expanding beyond verifying existing carbon credits to initiate their own forest projects—like the one in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley.

In keeping with the carbon market parameters outlined by groups such as Human Rights Watch, Pachama Originals projects focus on social benefits and biodiversity. They are using technology to enhance project design, track its performance, and bring better accuracy and efficiency to carbon credit issuance.

In keeping with the carbon market parameters outlined by groups such as Human Rights Watch, Pachama Originals projects focus on social benefits and biodiversity. They are using technology to enhance project design, track its performance, and bring better accuracy and efficiency to carbon credit issuance.

Another example of this work is Pachama’s Corridors for Life project in Pontal do Paranapanema, in southeast Brazil. Started in partnership with Mercado Libre in 2021, the project is showing signs of success.

“Today this project is providing jobs and we are starting to see the trees grow a few meters. Having such a visible impact is quite rewarding,” Aftalion said.

What’s Next

The next frontier, according to Aftalion, is applying generative AI to automate biomass verification. Though the technology is not there yet, Aftalion is optimistic.

“Many of the advances we recently saw in natural language processing through transformers will very rapidly translate into other areas such as point cloud processing, among others,” Aftalion said.

He has already seen what machine learning can do when applied to satellite imagery and remote sensing to measure biomass.

“We are not really that far away,” Aftalion said. “Going to CMU, you get this exposure to what can be done, and what people have done, and you feel that everything is possible.”

“We are not really that far away,” Aftalion said. “Going to CMU, you get this exposure to what can be done, and what people have done, and you feel that everything is possible.”

Aftalion’s dream isn't just about planting trees; it's about planting the seeds of a better future, and leveraging technology to get there.

“We stand at a pivotal moment in our industry as we make the transition to digital systems. It is a small step towards accounting for what really matters on Spaceship Earth,” Aftalion said.